Charting the Green River Watershed: A Journey Through History and Indigenous Knowledge

Writing and Research for this post by Zachary Pratt

1881 was a busy year for the Green River watershed as in the early part of the year, Virgil Bouge charted a route over Stampede Pass. This success for the Northern Pacific Railroad would open the opportunity to build a suitable rail line and close the final gap in the railroad’s cross-country route.

Very, very, very little was known about the area prior to 1870 by white settlers. It wouldn’t be until exploration and ‘discovery’ of coal in the area brought attention to the proposed economics of the area. Between the massive layers of coal built up in the last 45 million years and the tall dark forests that hid the ‘black diamonds’, opening this area to use of these resources would be a difficult, expensive and sometimes tragic undertaking.

While much of the path was paved with trial and error, Bouge’s travels through the uncharted areas of Southeast King County utilized a combination of luck, engineering experience, observations from local homesteaders and perhaps most useful, the Indigenous population who had lived among the hollers and hills since time in immemorial.

Photo: Virgil Bouge

Bouge began his travels by gaining a general understanding of the landscape. Visual observations can only get one so far, so going towards the Muckleshoot Reservation gave the party insight into what they were up against. Bouge writes:

“Some of their number once crossed the jungle described, reaching Mt. Enemclaw, a great cliff at the base of the foot-hills. But beyond that point no living Indian had ever penetrated. There was, however, a tradition of a trip made by one of their ancestors to the headwaters of Green River, where he found a pleasant country and good fishing.”

While the mention of “no living Indian had ever penetrated”, evidence of this trek being made was found and noted in the 1999 Howard Hanson Dam Master Plan. An abundant amount of precontact sites were found upon research into inundated lands by the reservoir, put into place as flood control for the Kent/Auburn Valley. The report states:

“Benson and Moura identified 14 prehistoric hunter-gatherer sites between elevations 1,100 and 1,141 feet, primarily clustered at the confluence of the main stem Green River and the North Fork of the Green River… Several other sites were recorded, literally, as they were being inundated by the seasonal pool raise, leading archaeologists to surmise there might be sites below the 1,100-foot elevation.”

To consider that, according to the US Army Corps of Engineers, “Lake elevation varies from 1,035 feet (invert of outlet tunnel) to 1,206 feet (top of spillway gates).” This shows there is a large amount of unexplored area that could easily make the fourteen confirmed sites swell quite rapidly. While the report does state that many of the sites have been overlaid with now feet of lake material build up, the simple fact that sites were being found, after almost 40 years (with the dam being opened in 1961), shows that there is still an absolute certainty that these sites could still be visited with the right conditions and time. This however is a tangent, as the site in question exists just six miles away as the crow flies, downstream of the dam.

The local knowledge obtained over thousands of years in the area was a primary reason that Bouge was able to chart this route. During his traverse of the area, two Indigenous guides were hired by the work party, from the Muckleshoot, referred to by Bouge as Peter and Charley. Based on the stories told of traveling to the area and physical sites found at Eagle Gorge and Howard Hanson, there is no doubt that precontact people both traveled through the area utilizing resources and more than likely, even if temporary, lived in the area. With this, Bouge would have traveled these paths laid out by those who had gone before him as the knowledge was shared and shown to him. In the years after the charting, coal mining towns would pop up throughout the area, as well as more homesteads and logging operations, thus adding to the already 45-million-year history.

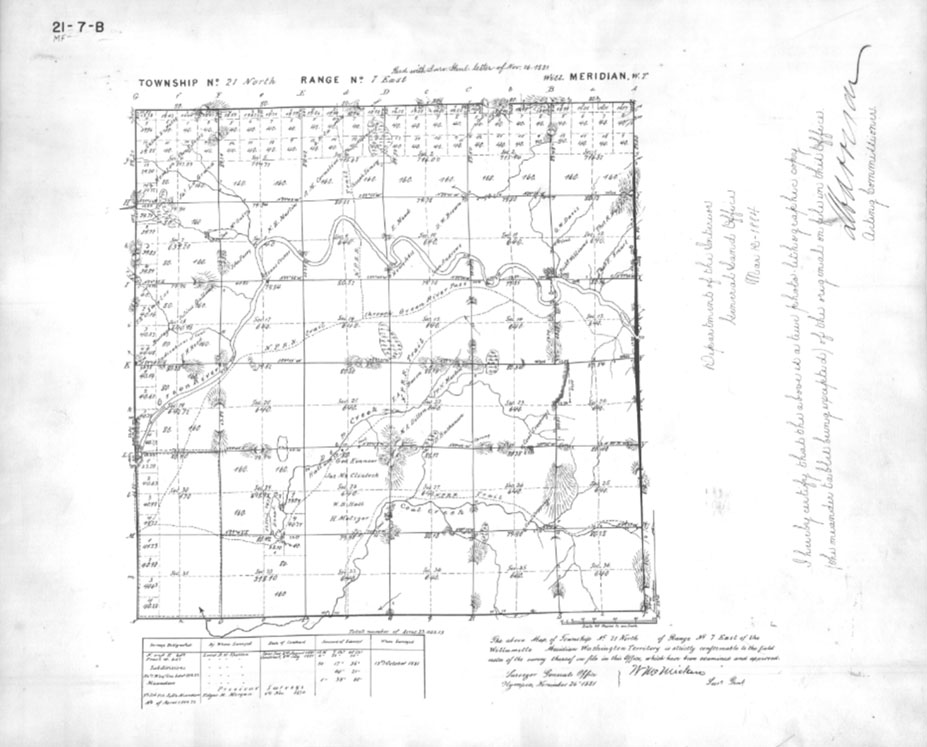

As shown on the Bureau of Land Management’s early GLO plat maps, identified as T21N R7E and recorded on 10/13/1881, two trails were cut by the Northern Pacific Railroad. These were utilized to transport men and tools to clear a path. Upon leaving the designated terminus of Tacoma, the path traveled across the Enumclaw Plateau. This trail can be tracked on plats T20N R7E AND T20N R6E to the city of Enumclaw.

Upon arriving on the designated map (T21N R7E), the surveyors show one trail splitting into two. This split occurs roughly where the Hanging Gardens is today. One trail takes a hard east turn immediately, before meeting Deep Lake, then tracking north through what we know today as Cumberland and the former site of Bayne. This follows closely to the modern road of Cumberland Kanaskat Road. The other constructed trail stays north, following the modern Enumclaw-Franklin Road. Near the present-day Green River Gorge Spring and Resort, the trail turns east. Its drifting course takes it across sections 17 and 16, passing just to the immediate north of Lizard Mountain before meeting with the other trail near Palmer Junction.

It’s interesting to note, on the east boundary of section 16 and 15, at the base of Lizard Mountain, a marsh is marked to exist. In a future date, upon discovery, the Occidental Coal Mine would find out about the source of this water the hard way. In 1910, the mining company drilled into a glacial spring inside of Lizard Mountain. As with many mines in the area, ground water penetration was a major issue facing miners. A former Cumberland resident and local explorer has credit to locating this water and its source in the modern drainage pattern. Discovered through several hours of ground survey, aerial imaging and LIDAR mapping, the water exits the hillside, traveling in a northeasterly direction towards Kanaskat Palmer State Park and south east towards Cumberland.

With an understanding that indigenous people did more than just pass through the area from Cumberland to Eagle Gorge, it’s difficult to gloss over the simple fact that this is a history that needs much more study and time to be better understood.

A grave concern, and often major mistake is the differing ideals that much of the Western construction, mining or general building practices have. The idea of a “dig first, ask questions later” mentality.

Just because a spot doesn’t have the markings of what the naked, untrained eye can see, when buckets full of material are removed, hauled away and crushed, it discounts and disrespects the material already removed and takes away that historical record.

While not every grain of dirt can be sifted through, to simply forgo the idea of a major site being thoroughly studied a huge disservice to the people of the past and the better understanding for the future.

Sources:

Bogue, V. G. (1895). Stampede Pass, Cascade Range, Washington. Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York, 27(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.2307/197311

Evans, G. W. (1912). The Coal Fields of King County (p. 182). E. L. BOARDMAN, PUBLIC PRINTER.

Shelton, L. D. W., & Morgan, E. M. (1881). Georeferenced General Land Office Plat Map Cadastral Survey 21-7E-B Township 21 North, Range 7 East, Willamette Meridian, WA [Review of Georeferenced General Land Office Plat Map Cadastral Survey 21-7E-B Township 21 North, Range 7 East, Willamette Meridian, WA]. https://riverhistory.ess.washington.edu/duw_puy/glo/framedex.htm

Wilson, J. G., Fiske, J., Dick, C., & Homans, J. E. (1918). The Cyclopaedia of American biography. In J. E. Homan (Ed.), Internet Archive (Vol. VIII). New York Press Association Compilers. https://archive.org/details/cyclopaediaofame08wilsuoft/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater

Yorozu, P., Et.al. (1999). Howard A. Hanson Master Plan (pp. 35–36) [Review of Howard A. Hanson Master Plan]. US Army Corps of Engineers. https://planning.erdc.dren.mil/toolbox/library/ChiefReports/Howard%20Hanson%20Dam,%20WA%2013%20Aug%2099.pdf